Providence and the Pandemic

Martin Thielen

January 4, 2021

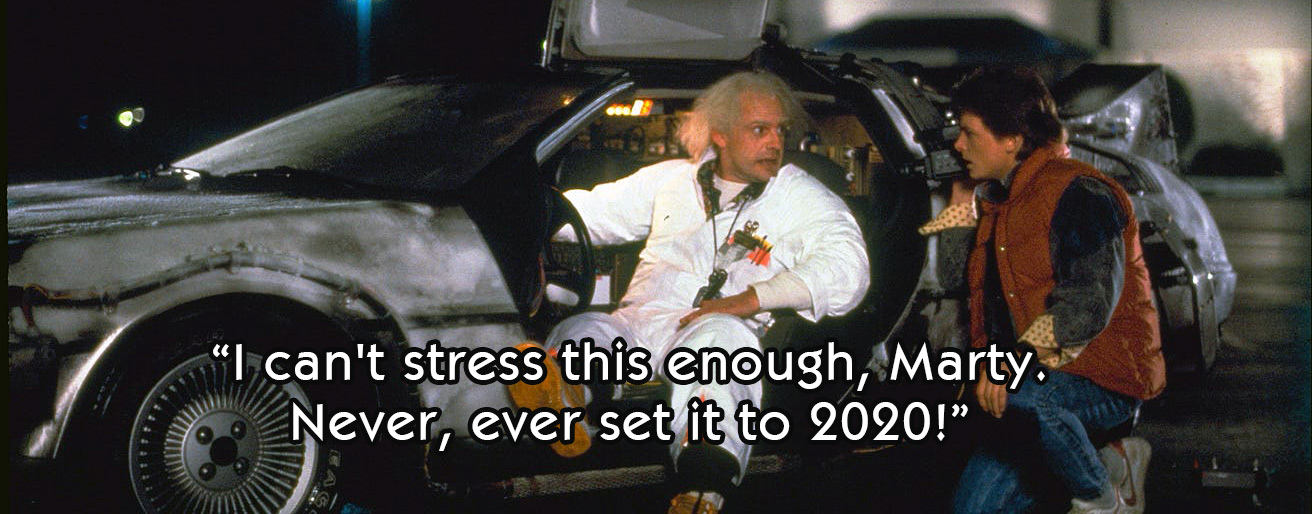

Near the end of 2020, I received a text message with an image from the classic film, Back to the Future. In the scene Doc Brown shows Marty McFly how to set time travel dates on his iconic DeLorean time machine. He says, “I can’t stress this enough, Marty. Never, ever set it to 2020.”

No sane time traveler would purposely choose to visit the year 2020. The events of that cataclysmic year included a worldwide deadly pandemic, apocalyptic wildfires, massive hurricanes, overwhelming political turmoil, divisive racial strife, painful economic upheaval, gross inequities, and dangerous threats to democracy. By December 2020, a divided country all agreed on at least one thing—2020 could not come to an end soon enough.

However, as bad as 2020 proved, it wasn’t unique in human history. Many years have brought similar pain and suffering. All of which begs the question: Is it still possible to believe in divine providence? Can people of faith still see God’s hand in history? Does God really intervene in human and natural affairs? At least three competing answers to that question are possible.

Retaining Providence

In spite of pandemics and other disasters, most people of faith retain a traditional view of providence. They continue to believe in an all-powerful God who supernaturally intervenes in history and providentially cares for creation, both individually and universally. Advocates of this view often say things like, “God is still in control.” “God’s got this.” God has a purpose.” And, “God works in mysterious ways.”

However, this cohort of believers is shrinking. For example, in a 1990 poll, three quarters of Americans said they believed in an “all-powerful Creator who rules the world.” In 2020, only one-half of Americans affirmed that belief. Although a traditional view of providence is still the default setting for most American believers, its popularity is rapidly diminishing.

Rejecting Providence

Plenty of people, both religious and nonreligious, reject belief in providence. In short, they have abandoned the notion of an interventionalist God who works miracles and answers prayers. For some, this loss of faith in God’s providential care is rooted in painful personal experiences.

For example, when she was a child, singer Iris Dement’s young brother fell down the stairs of their home and sustained critical injuries. Her parents rushed him off to the hospital. She stayed home and prayed all through the evening. She even skipped dinner, pleading with God to save her little brother. But in the end he died. Years later she wrote a song about the experience. She called it, “The Night I Learned How Not to Pray.”

Like Iris Dement, millions of people look around at the universe and see overwhelming and brutal suffering, both in the natural world and in human history. Their conclusion? God—if God exists at all—does not providentially care for creation.

Redefining Providence

In a world of pandemics, cancer, Alzheimer’s, hurricanes, tsunamis, and massive injustices of all kinds, maintaining a traditional view of providence has become impossible for many believers. After observing endless prayers for miracles that never occur, their only viable conclusion is that God does not work in the universe through supernatural intervention.

That conclusion does not require an atheistic worldview or even a rejection of providence. However, in order to maintain intellectual integrity, it does require a redefined concept of providence. For a growing number of progressive Christians, this means an affirmation of natural providence rather than supernatural providence.

People who affirm natural providence believe that God works in the universe through natural and organic ways, including the ongoing process of evolution. Instead of seeing a “supernatural” God, they envision more of a “super natural” God. They believe that God, rather than breaking natural laws, works exclusively within them.

Natural providence also affirms—as Christian tradition has long taught—that God works through human instruments. For those inclined to believe that possibility, supporting evidence abounds, even during a pandemic. Think of frontline workers, scientists who developed vaccines in record time, and even lawmakers who approved massive financial stimulus packages.

For example, during the pandemic, a newspaper deliveryman in New Jersey offered to help his senior adult customers with grocery deliveries. Large numbers of them took him up on his offer. He and members of his family have supplied more than 140 homes and conducted more than a thousand grocery runs, and they are still at it. He said, “Other than raising my three kids, it’s been the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done.” One does not need to believe in God to explain this kind of compassionate service. But, for those with eyes to see, it looks a lot like God at work through natural providence.

Many religious people will strongly disagree with a nonsupernatural understanding of providence. And many nonreligious people will reject the idea of a God who providentially works in the universe through natural organic means. Either group of critics—traditional believers or unbelievers—could be right. This premise certainly can’t be proven. However, a theology of natural providence rather than supernatural providence is a reasonable possibility and worthy of consideration by thinking Christians in the modern era.