The God I Don’t Believe In

By Martin Thielen

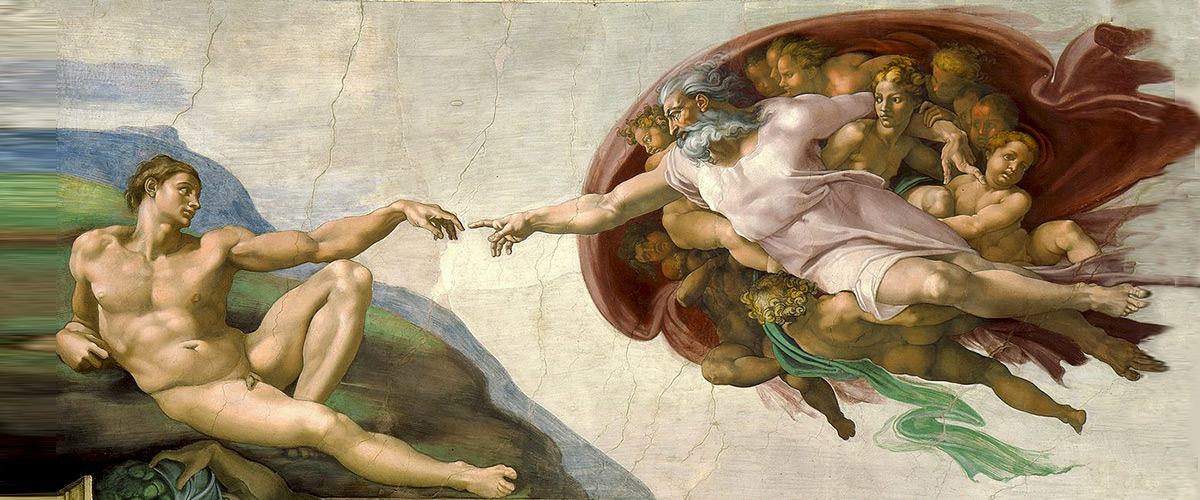

Michelangelo (1508–1512), The Creation of Adam, fresco, Sistine Chapel ceiling, Vatican City

November 4, 2025

Years ago, when I served as a parish pastor, I visited an inactive member of my new congregation. Although he used to attend regularly, after his wife died, he quit coming. By the time I arrived at the church, he had not attended worship for several years. During our visit I said, “The congregation and I would love for you and your children to return to church.”

He said, “Thanks for the invitation, but I don’t believe in God anymore.”

I said, “Tell me about the God you don’t believe in.”

He then told me his story. Years earlier, he, his wife, and their two young children came to church every Sunday. But then his wife developed breast cancer. In spite of all their prayers and the best medical treatment available, she only got worse. He begged God to save her, but she died anyway. He told me, “When I buried my wife, I also buried my faith. I don’t believe in a God who kills twenty-eight-year-old mothers with cancer.”

I replied, “I don’t believe in that kind of God either.”

In this month’s post, I’d like to tell you about the God I don’t believe in. In my next post, I’ll tell you about the God I do believe in.

I Don’t Believe in an Exclusive God

Although it happened decades ago, I still vividly remember a Sunday school class lesson I attended during high school. A missionary from another country was speaking. He told us it was imperative that we send more missionaries around the world because people who did not accept Jesus as their Lord and Savior were lost and had no hope of salvation in this life or the next.

I asked the missionary, “What about people who’ve never heard of Christ?” He said, “They will die, lost in their sins, and spend eternity separated from God in a devil’s hell.” I said, “You’re kidding.” But he wasn’t kidding. And while I didn’t challenge him, I didn’t buy it. I still don’t.

According to Pew Research Center, 29 percent of the world’s population is Christian. Twenty-four percent have no religion. The other 47 percent are non-Christian believers including Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and Jews. To claim that Christianity is the only way to God and that 71 percent of the world’s non-Christian population is “lost” without any hope in this life (or the next) is intolerable theological arrogance. Surely the life-giving God of the universe is not a petty and jealous tribal deity who spitefully rejects the vast majority of humanity.

I Don’t Believe in a “Hell Fire and Damnation” God

I once read a troubling news story about the unimaginable cruelty of ISIS terrorists, including sexual violence, chopping off hands, death by stoning, and beheadings. In one documented incident, Islamic State soldiers placed one of their prisoners in a cage, saturated him with gasoline, set him on fire, cheered as he died in agony, and then posted a video of the execution online. It was one of the most depraved acts of human cruelty I’ve ever heard of.

But if hell is a literal reality, God is far worse than those ISIS terrorists. They only burn their victims for a few minutes until death brings welcome relief. If the traditional doctrine of hell is true, God burns his victims in agony for all eternity, with no hope of relief—ever.

A theology of hell depicts God as a cruel, vengeful, vile, psychopathic God who sadistically and eternally tortures people for holding erroneous doctrines about Jesus. I believe this view of God is nothing less than theological pornography. As Charles Templeton vividly articulated, “The idea of an endless hell is a monstrous concept. That a so-called loving Father would condemn his children . . . to be tortured forever, with no hope for reprieve, is barbarous beyond belief and can only be dismissed as ancient sadistic nonsense.”

I Don’t Believe in a Protector God

For decades, I wanted to believe in a providential God who protects people from harm. But after decades of seeing the opposite reality play out, I finally gave up on the idea.

For example, over a decade ago, when a close friend of mine was crushed and killed in a horrific car wreck, along with his wife and two young children, I wrote in my journal, “It wouldn’t have taken much to prevent this disaster. Just a few seconds of the truck driver’s foot on his brake before he slammed into them. That’s all it would take. Surely an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-loving God could pull off something as simple as that. You would think so. But you would be wrong. In this case, dead wrong. Times four.”

At that point in my life, I was still trying to believe that God providentially cared for people. But it was rapidly becoming a losing battle. In a world full of unrelenting and massive suffering, including accidents, disease, war, violence, famine, genocide, pandemics, birth defects, child abuse, hurricanes, earthquakes, tornados, tsunamis, and dementia, it became impossible for me to believe in an interventionist, miracle-working, prayer-answering, providential protector God. Instead, I finally (but reluctantly) accepted the death of providence.

I Don’t Believe in a Religious Right God

When it comes to the nature of God, the religious right gets it wrong. I do not, will not, and cannot believe in the antigay, anti-immigrant, antiscience, anti-Muslim, antiwomen, anti-intellectual, antiwoke, angry, intolerant, negative, judgmental, narrow-minded, militaristic, overtly partisan, hypernationalistic, and mean-spirited God promoted by many (not all) of today’s extreme religious-right believers.

This misguided but widely held concept of God clearly contradicts the example, teachings, and spirit of Jesus. It has also turned millions of people away from Christ and the church. I completely reject this toxic view of God and encourage you to do the same.

Much more could be said about the kind of God I don’t believe in. For example, I don’t believe in a God who is concerned about personal salvation but unconcerned about social justice. However, the above examples are enough to make the point—a lot of our God concepts need to be reevaluated. And some of them need to be rejected.

Before concluding this article, I’d like to review one more model of God that I don’t believe in. I used to believe in this kind of God. And I held that belief for a long time. But I am no longer able to do so.

I Don’t Believe in “The Man Upstairs” God

In his book God: A Human History, Reza Aslan accurately notes that for the vast majority of people, “God is a divine version of ourselves: a human being but with superhuman powers.” In the words of Brian McClaren, a lot of folks conceptualize God as “an old big white guy on a throne in the sky.” But for a rapidly growing number of people in the twenty-first century, “the man upstairs” God is no longer adequate.

A few years ago I read a compelling book called Saving God from Religion by Robin Meyers. In the book, Meyers tells a story about attending an art class during college. During the class the professor showed slides of Michelangelo’s magnificent frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The last slide featured the chapel’s most famous painting, The Creation of Adam. In it, God is depicted as an elderly white and bearded man, wrapped in a swirling cloak, reaching his right arm toward Adam, his greatest creation (see image at top of this page).

Years later, Robin Meyers had a dream about that famous painting. In the dream, he served as caretaker for the Sistine Chapel. One day he heard a loud crash in the chapel. He quickly ran inside. On the floor, in a thousand pieces, was all that remained of the most famous fresco in the world. He looked up to the ceiling. The plaster where Michelangelo’s image of God had been fixed for five hundred years had broken lose and fallen to the floor. God had fallen off the ceiling. The painting was completely destroyed and could never be repaired.

Meyers used that story as the overarching metaphor of his book. The traditional theistic “man upstairs” God of orthodox Christianity, argued Meyers, is no longer viable. He admitted that “the loss of such a deity poses an existential threat to the religious franchise. Yet our survival now depends upon the death of Michelangelo’s God. He cannot be put back together again, much less reattached to the ceiling of a world that no longer exists.” In short, Meyers claims that God—as we have historically understood God—no longer exists.

In recent years, after decades of angst and struggle, I finally acknowledged that my long-held faith in a traditional theistic God was gone and never coming back. Michelangelo’s orthodox view of a personal, powerful, providential, supernatural, external, interventionalist, humanlike, parental “man upstairs” God who’s “got the whole world in his hands” had fallen from the sky and smashed into smithereens. It was time for me to develop a new understanding of God.

Of course, the above comments about the kind of God I don’t believe in raise an obvious question. If I no longer affirm faith in a traditional theistic God, what kind of God do I believe in? I’ll grapple with that question in my next post.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

To share this post, please click the appropriate icon at the bottom of the page. If you would like to communicate with me, feel free to send an email and I’ll respond as soon as possible. To receive my monthly newsletter (a brief email notification alerting you to new posts and other materials), please do so today. Thank you for your interest in Doubter’s Parish. Writing for you is a joy.